Beyond Data Collection: The Transformative Role of Citizen Science in Public Engagement

Title: Exploring scientists’ perceptions of citizen science for public engagement with science

Author(s) and Year: Stephanie A. Collins, Miriam Sullivan, Heather J. Bray; 2022

Journal: Journal of Science Communication

TL;DR: Past studies on citizen science, enlisting the public to collect scientific data, has focused on its use as a research method. Here, the authors change this perspective and relay insights into how citizen science can be used as a mode of science communication, by directly engaging the public with scientists.

Why I chose this paper: While listening to a podcast about the Flint Water Crisis, I heard the term “citizen science” and wanted to learn more about how it has been used in combination with research to increase public awareness about science.

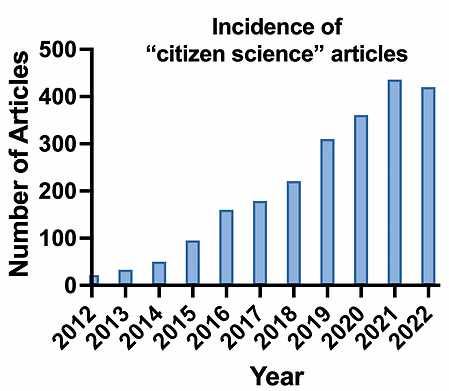

Nine years ago, the lives of the citizens in Flint, Michigan changed forever because of a faulty water system, but it would be one whole year until they uncovered the reason behind it. In April 2014, the Flint water supply was switched to the Flint River as a cost-saving measure. Built up corrosion in the old pipes, however, quickly led to the spread of lead and bacteria throughout the city. Despite Flint residents noting changes in their tap water and their health, complaints were ignored by city officials. It took a collaborative effort between scientists at Virginia Tech and Flint residents – using citizen science to collect water data – to expose the Flint Water Crisis, forcing officials to recognize and amend their mistake. In the last decade, the use of citizen science in research studies has increased in popularity (Figure 1).

The Details

Past analysis into the method of citizen science has found that scientists primarily recognize it as a tool for data collection. But, it is important to note that it also has a social aspect – the public is actively engaging in scientific research. Few citizen science evaluation studies, however, acknowledge this latter point and focus solely on its use in data collection.

Other studies surrounding scientists’ perceptions of citizen science suggest that many feel that the data is of lower quality and less trustworthy despite studies showing that it can be as accurate as data collection requiring formal science training, like how to identify plant species in a given area, for example.

Given that citizen science places the public in the “hot seat” of research, it is tempting to wonder if increasing involvement of the public in data collection could help with public engagement in science, leading to societal benefits such as more science policy measures and awareness of environmental conservation efforts.

The Study

Science communication specialists at the University of Western Australia and Edith Cowan University (Australia) recognized that most studies on citizen science projects emphasize how volunteers can be used to collect data rather than investigating citizen science as a tool for public engagement in research. In this study, the authors strive to understand scientists’ attitudes towards citizen science as a mode of public engagement. Their goal was to provide insights into citizen science projects and help improve the design process, showcasing its full potential for science communication.

Methods

Nineteen biologists in Australia, 10 with previous experience using citizen science in their research and 9 without, participated in Zoom interviews answering questions related to citizen science and public engagement. The interviews were transcribed and analyzed for common themes using a qualitative analysis software. In order to ensure validity, the first author also interpreted interview responses and found the same common themes. The biologists varied in disciplines ranging from botany to marine biology and career stage, which was considered in the results.

Results

First, when asked to define citizen science, 18 of the 19 scientists said it involves non-scientists in science, and 11 used the term “data collection.” Most of the participants thought predominantly about the research aspect of citizen science. Interestingly, only one participant gave a definition including the potential of citizen science to promote public awareness and understanding of research.

When asked about their opinion of public engagement through citizen science, half of the scientists agreed that it could be useful for stopping misinformation and building trust between the public and science.

Overall, identified benefits of citizen science participation fell into three main categories: knowledge-based, societal, and experiential.

Knowledge-based – Participation could influence participants to pursue science careers and/or act as a valuable learning opportunity for students already studying science.

Societal – Volunteers could disseminate information from their study experiences, influencing their social circles’ perceptions of science, leading to more support for science policy changes in local governments.

Experiential – Participants may gain a newfound appreciation for the scientific method and learn about the importance of research, while having a good time doing it.

The Impact

As the use of citizen science in research continues to grow in popularity (Figure 1), so does the potential for scientists to engage the public with their research. This creates a physical connection between the research and the public, which in turn, gives science communicators a more understanding and captive audience.

In the future, it will be important to evaluate the design and outcomes of citizen science projects on volunteers and the community, rather than just the data. If scientists can keep public engagement in mind when designing studies, there will be a higher chance that we communicators can also benefit from their work – jumping off where the data collection ends, and the talk about science begins.

Edited by: Rebecca Dang and Niveen Abi Ghannam

Cover image credit: Pixabay: RosZie