Changing COVID vaccine skepticism—one mind at a time

By Tony Van Witsen

Title: Cutting the Bunk: Comparing the Solo and Aggregate Effects of Prebunking and Debunking Covid-19 Vaccine Misinformation

Author(s) and Year: Michelle A. Amazeen, Arunima Krishna, Rob Eschmann, 2022

Journal: Science Communication

TL;DR: Debunking has emerged as a popular way to counter false scientific beliefs–that is, exposing skeptics to the fact that they may be misinformed. But there’s a lot of disagreement over how to do it best. The authors investigate the process of changing minds through corrective messages and find it works in many different ways. They conclude the strategy needs to be tailored to different individuals with different beliefs.

Why I chose this paper: I’m drawn to research that cuts through myths and simple explanations and shows how complex and varied communication is and how many different ways our minds respond to messages.

The problem

“Infodemic” is the word coined by the United Nations World Health Organization (WHO) in 2020 to describe the contagion of misinformation that accompanied the COVID-19 pandemic. Just as worldwide jet travel accelerated the spread of viruses, accelerating social media sent outdated, misleading and downright false knowledge around the world at the speed of a mouse click. Not surprising, then, that evidence shows the most seriously misinformed among us are those with the most social media presence.

The research

Tempting as it is to just set people straight with the facts, this debunking strategy rarely works consistently or well in practice. New research by Michelle A. Amazeen and Arunima Krishna of Boston University along with Rob Eschmann of Columbia showed just how complicated it is to change minds. The process of “debunking,” as it’s called, usually means providing detailed facts to show why people are misinformed and what’s really true. But misinformation can be stubborn and linger in peoples’ minds even after efforts to correct it.

Current best practices call for pre-emptive interventions called “prebunking.” This means taking the time and trouble to explain the aspects of misinformation that can mislead people such as inaccurate sources or flaws in logic. Some communication researchers call this “inoculation,” after the vaccination process. Instead of injecting a weakened virus to help the immune system, inoculation sends a two-part message aimed at countering false arguments: first a warning that a new argument is coming, then actual reasons why the false belief is wrong. The principle is that you can’t change minds by simply telling people they’re wrong. You also need to repeat the false claims, like the weakened version of a virus in a vaccine, then immediately offer a counter message people can use to generate a new narrative in their own minds.

That was the theory, anyway, one so widely accepted that it showed signs of becoming accepted wisdom. As recently as 2017, the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania proclaimed, “it’s no use simply telling people they have their facts wrong. To be more effective at correcting misinformation in news accounts and intentionally misleading “fake news,” you need to provide a detailed counter-message with new information — and get your audience to help develop a new narrative.”

Amazeen and colleagues suspected the whole truth didn’t always work so neatly in practice. They were especially interested in the inner psychological processes of changing minds, especially the sense of threat people may feel when new information challenges what they thought was true. Do they accept the new message or go into defensive mode and resist?

Method

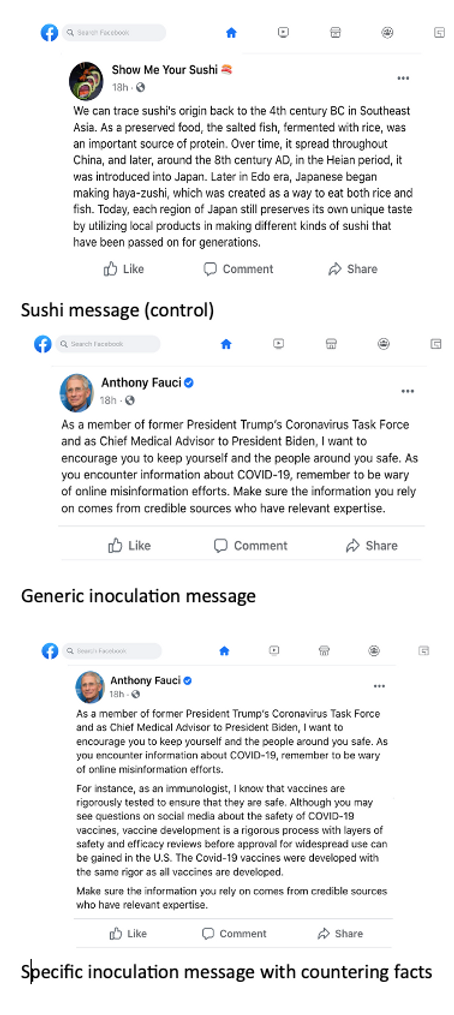

Seeking answers, they administered a series of test messages to 540 Americans. To test the inoculation process, they gave some subjects a generic inoculation message in the form of a simulated Facebook post from Dr. Anthony Fauci about COVID vaccine misinformation. (Fig. 1) Others got a specific inoculation message from Dr. Fauci with explicit reasons why COVID vaccines are safe. A third group received a generic message about sushi as a control.

Fig. 1: Inoculation messages

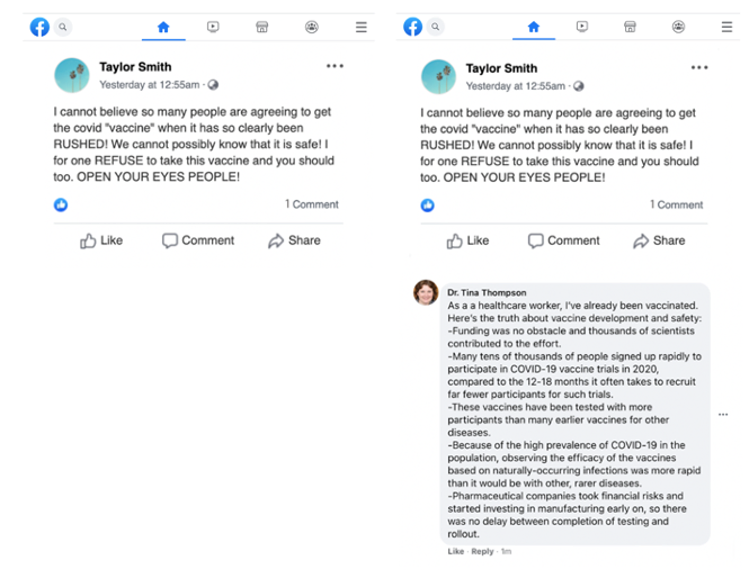

To test the debunking process alone, they administered a second set of messages which included pure misinformation. (Fig. 2) One was a post from an imaginary “Taylor Smith” claiming COVID vaccines were developed so quickly they couldn’t be safe. “I, for one, REFUSE to take this vaccine and you should too.” An alternative message included the same screed along with a bulleted list of five reasons why “Taylor” was wrong. All subjects answered questions about their attitudes toward misinformation. Did they find misinformation threatening? Scary? Dangerous? None of the above?

Fig. 2: Debunking messages (with and without facts refuting “Taylor’s” claim)

The results showed how many different mental paths people took in response to these complex messages. Inoculation messages that didn’t try to counteract the misinformation worked best on people with moderate attitudes toward vaccines, increasing their likelihood of being vaccinated. Those that did contain counterarguments from “Dr. Fauci” worked especially well on people who already had pro-vaccine attitudes and were inclined to find misinformation untrue. Those who were skeptical to begin with tended to see misinformation as more accurate, not less, which lowered their chances of being vaccinated. Interestingly, generic messages actually worked better on skeptics than those with counterarguments, though it wasn’t clear why. The authors found having positive or negative attitudes toward COVID vaccines didn’t affect peoples’ perception that the debunking messages threatened their prior beliefs, no matter what the message. They suspect their subjects’ response to new and threatening information about vaccines may have more layers than previous researchers believed, triggering both motivational and emotional responses at the same time.

Conclusions

The authors concluded there’s no one-size-fits-all prebunking message that can work for everyone. Pre-existing attitudes made a big difference in the effectiveness of messages, yet the kinds of messages made a difference too. Inoculation messages with specific counter-information worked best with those who had healthy attitudes more likely to be persuaded. The more generic messages — the ones that didn’t contain counter-information from “Dr. Fauci”— had preserved existing beliefs in those with pro-vaccine attitudes. They also changed beliefs in those with anti-vaccine attitudes but these benefits disappeared when debunking messages were used. Overall, they believe their findings add another layer to the complexity of persuasion and emphasize once again the importance of knowing one’s audience. A key task is to better understand the circumstances that cause inoculation messages to change minds, or fail to.

Edited by: Sarah Ferguson, Niveen Abi Ghannam

Cover image credit: Unsplash/D. J. Paine