Communicating risky science when the public isn’t inclined to trust

By Tony Van Witsen

Title: Heuristic responses to pandemic uncertainty: Practicable communication strategies of “reasoned transparency” to aid public reception of changing

science

Author(s) and Year: Jaigris Hodson, Darren Reid, George Veletsianos, Shandell Houlden, Christiani Thompson, 2023

Journal: Public Understanding of Science

TL;DR: Public health decision makers and communicators may have a very difficult time establishing trust in their recommendations in the midst of a pandemic, when the science is still unsettled, particularly for masks and vaccination. Should they emphasize uncertainty, which might confuse people? Play down the uncertainty, which might cause distrust when the science changes? Hodson and colleagues studied the ways people respond to uncertain information to create guidelines for communicating uncertainty. They employ a concept they call “reasoned transparency,” which aims at preparing people to expect science to continuously change.

Why I chose this paper: Public mistrust of science has been growing for decades. The pandemic created circumstances almost custom-built to amplify this mistrust. The search for better ways to communicate public health decisions based on incomplete and uncertain information has been slow, yet it seems important to me to find better ways, however imperfect, to close the trust gap.

To mask or not to mask? Anyone who lived through the last three years of pandemic-related advice might be forgiven for wondering, as official guidelines of masking changed again and again. “No” from authorities such as Dr. Anthony Fauci in the pandemic’s first days, then “yes,” when mask guidelines were imposed in April 2020. A year later, as COVID vaccination incidence increased, the Centers For Disease Control (CDC) said fully vaccinated individuals did not need to wear masks or physically distance when in public. The shifting federal guidelines, on top of a patchwork of local mask mandates, caused more than confusion. Some wondered if public health authorities were acting capriciously or basing their decisions on any science at all.

It was a challenge for officials such as Fauci who had to find ways to be open and honest about the changing science behind the guidelines without confusing people or losing public trust. Science is always uncertain and the science behind masking turbocharged that uncertainty, with frequent shifts and updates as new research results emerged during the course of the pandemic. Communicating all this clearly was a slippery task at best, with no firm rules or principles. Some think all uncertainties should be made clear, even emphasized. Others say uncertainty should be suppressed because the public doesn’t know how to deal with the nuanced complexities of scientific research.

Both these approaches played out in 2009, during the H1N1 pandemic. In Australia, health officials first said the virus was dangerous to everyone. When the science changed, they began stating the virus was only dangerous to some people without explaining why their message had changed. The lack of transparency led to a backlash. In Toronto at the same time, where officials emphasized the uncertainty of their knowledge, some people lost confidence in the public health establishment. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t. What’s a poor, pressured public health officer to do?

The Study

Seeking some evidence-based answers, Jaigris Hodson of Royal Roads University in Canada and colleagues tested a middle path they call “reasoned transparency,” based on the ways people interpret uncertain information about both face masks and vaccines. Focusing on 27 Canadian adults, they used a method called elicitation interviewing, which guides participants back toward recalling or re-living an experience in order to reconstruct a detailed account of how they thought about it. Because all the subjects had recently engaged with COVID-19 information online, the interviewers looked for heuristics, the simple mental shortcuts people use to make sense of a complicated situation, such as uncertain and risky science. The interviewer exposed participants to a pair of Facebook posts from the World Health Organization (WHO) about masks and vaccines, then, for each post (Fig. 1), asked:

How would you respond if in the future researchers find out that this information is actually untrue or inaccurate?

In constructing the question, the researchers worked on the belief that if they asked people how they responded to past changes in science, their answers would reflect a wide range of inputs, while their response to hypothetical future changes would more likely reflect their heuristic shortcuts. They based this on psychological research showing that hypothetical questions have the advantage of limiting real-world responses and allowing access to the less conscious or rational components of peoples’ judgments.

The Results

They found that while people gave many reasons for their answers, the predominant judgments were based on four key heuristic cues: affect (emotion), trust in science, appeals to tradition, and expectations about science and the world around them. When people based decisions on emotions and tradition, their responses to change were negative. Emotion in particular led to rejection or resistance to scientific change, and so did tradition.

When asked, “If in the future, researchers find out this information about masks is actually untrue or inaccurate, how would you respond?” subjects made statements like:

Masks have been worn for a long time in health care,

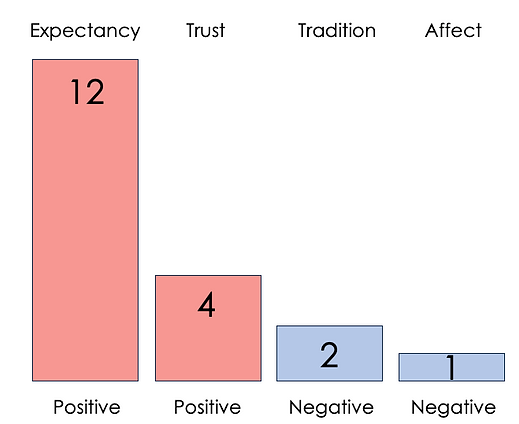

Trust and expectancy tended toward positive responses to change. One participant said he would accept changing face-mask science if it came from a reputable source like the World Health Organization (WHO). Expectancy was the dominant heuristic cue on both masks and vaccines, but it didn’t drive decision making in one direction. Instead, people looked for evidence of whether or not the new information conformed to what they had previously expected, depending on who provided the information, how it was formatted, or its content. These factors influenced trust or mistrust. For face masks, more responses were driven by expectancy (12) and trust (4). (Fig. 2) Subjects tended to respond positively because they expected science to change. One respondent put it this way:

I wouldn’t be personally too bothered because I can respect and understand that science as a field of knowledge is ever changing.

Emotions such as fear, anger and frustration were present, but played a smaller role than the researchers believed they would.

In face mask science, the most common heuristic cues after expectancy was trust, followed by tradition, then affect. Thus positive cues far outweighed negative cues.

The dominance of positive heuristics such as expectancy (12 responses) and trust (4 responses) indicated most participants had a positive response to changing mask science. One subject understood how how more research can lead to changes in science and how we need to adapt to it:

I think we all don’t like when the rules change or when the information changes, but the fact of the matter is as we do more research, things can happen like that in science. So we adjust and we take the new information and do our best with it.

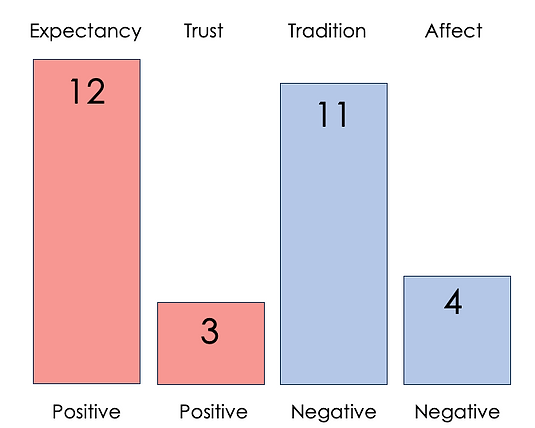

In vaccine science by contrast, many participants expressed their rejection of hypothetical changes even when they understood perfectly well that science changes all the time. An equal number of responses were driven by negative heuristics of tradition (11) and affect (4) as by expectancy (12) and trust (3). (Fig. 3)

Apparently their perception of the long standing nature of vaccine science overrode their recognition of change. One participant said:

I think that as science evolves, you know, our views on things change and we adjust.

At the same time this subject emphasized that she would be unwilling to acknowledge changes to vaccine science:

Because it’s been working for a long time.

The Impact

What lessons can science communicators draw from the patterns in this complex mix of responses? The authors say their findings represent another nail in the coffin of the discredited “information deficit model” in which people can be trusted to do the right thing simply by having all the information. Communicators need to be critically aware of how messages are perceived, not only what content they think they are communicating. While the authors believe there’s still much to be learned, they have a few suggestions.

First they say it’s important to use powerful narratives about the inevitability of change in science. They believe that scientific change means science is working as it should and reminding people of this can prime people to understand that change isn’t a problem in science. Second, officials and the communicators who work for them should recognize that talking about scientific change won’t work in all circumstances, especially when the old science has been around a long time and forms the background of peoples’ expectations. In such situations, it’s important to reconcile new messages with the old and explain why the old science (and the recommendations that grew out of it) was once seen as true and why it has now been replaced by something different.

Though these are useful guidelines, the authors still consider them preliminary. They say it’s equally important to learn the physical, emotional and psychological influences that shape peoples’ responses to pandemic-related communication. Making difficult judgments in a crisis is a complex task for both communicators and the public. The authors say focusing on a single influence will always be incomplete without addressing other factors at the same time.

Edited by: Caroline Cencer, Niveen Abi Ghannam

Cover image credit: Pavel Danilyuk (Pexels)