SciCommCon 2022 Coverage Part II

By Kirsten Giesbrecht

We’re back sharing some highlights from the UNL Center for Science and Mathematics Education’s SciCommCon 2022: Sharing Science in a Polarized World – don’t forget to read Part I here !

| TL;DR: We hear from three keynote speakers who share tools they use to connect to their communities, from intersecting science with pop culture, using empathy and psychology, to translating out of this world press releases into Blackfoot. Why I chose to attend SciCommCon: I wanted to learn how to approach wider audiences and communities. Attending the conference helped me understand how STEM professionals such as professors or engineers use science communication to reach broader audiences outside of the people they interact with on a daily basis. |

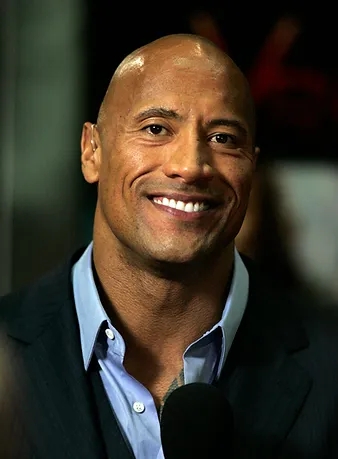

Dr. Raychelle Burks on Harnessing Social Media for SciComm: The Rock Test and Asset-Based Approach

Dr. Raychelle Burks, Professor of Analytical Chemistry at American University, started off her talk with her essential tip to “engage in social media like you’re talking to The Rock”. Yes, The Rock, as in Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson.

She calls it The Rock test, because The Rock has a huge following across multiple social media platforms. If she found herself in a hypothetical scenario where The Rock wanted her to talk about chemistry on Instagram she says,

“I would have my fan moment, right, but then I would talk to him as a fellow person of color”.

She adds that even though she feels like she knows him from his social media and cinematic appearances, he’s still a stranger. So she would also want to know what kind of chemistry he or his audience might want to learn about in order to tailor her talk.

Although The Rock test is her take home message for any science communication on social media, Dr. Burks also shared four key steps for those embarking onto science communication via social media for the first time. Using social media as a science communication platform can be intimidating at first, but you’ll be tweeting, tik-toking and engaging people with science on social media in no time by following these key principals.

1. Policy

- Know the social media policy of the place where you work

- Many institutions have established policies that are useful guides.

2. Strategize

- Ask what your goals are for doing science communication through social media

- Consider the resources you have, including your time and energy

- Establish a metric to determine if you are reaching your goals. Burks looks at engagement in tweets and how many times an article link was clicked

- Consult literature and research on communication and science communication. Some strategies can be social media platform specific or field of study specific. It’s normal to redevelop strategies or refocus them as your career develops

- Find the right tools. For instance, Burks found that it’s easy to engage with virtual posters in conferences on twitter, whereas instagram is better suited for following science-themed hashtags such as #fluorescencefriday.

3. Mindset : Dr. Burks considers this to be the most important key

- Focus on your mindset as you engage with your community and with other science communicators. Communicate with an open mind, ready to exchange ideas with your audience, rather than having a one-way flow of information

- Reflect if you’re approaching social media science communication from an inclusive mindset

- Consider an asset-based approach instead of a deficit model. In a deficit model, you assume the audience doesn’t know anything and that sharing knowledge with them will change their mind. An asset-based approach “recognizes that everyday knowledge, experiences, and cultural practices of audience members are their resources for learning.” Think of science communication as building and learning together, as engaging instead of preaching

- Dr. Burks has coauthored Broadening Participation Toolkit with these ideas

4. Comfort

- Don’t do too much. You don’t need to follow every piece of advice or be on every social media platform. Don’t change who you are to fit the platform. In fact, authenticity is an effective teaching and communication strategy

- Make sure you feel comfortable and safe emotionally, psychologically, and financially. It’s good to stretch and grow, and it’s normal to feel uncomfortable when you’re undergoing those changes, but also double check that you’re okay with that. If you aren’t then just don’t do it

- Being comfortable doesn’t mean being boring. Sometimes the most creative and engaging science communication on social media can occur when your comfort, research or project and pop culture align

Dr. Burks shares an example of a twitter post she made a few months ago. After posting about a synthetic dye used in fashion at the Met Gala, she reviewed the engagement analytics of the tweet. The analytics revealed she got many of her followers to click the link that led them to literature on the history of synthetic dyes. “They fell into my trap!“, she told us joyfully ( Reader, I fell for her trap too). The tweet passes The Rock test, too. She connects to a broad audience through a shared appreciation of admiring the Met Gala fashion, while infusing fascinating chemistry facts into their twitter feed. Who knows, maybe Dwayne himself learned about synthetic dyes that day.

Emily Calandrelli on Empathy: The Vomit Comet and Coal Fairytales

As the first woman to host a nationwide Emmy award winning science show, Xploration Station, as well as host and co-executive producer of Emily’s Wonder Lab, Emily Calandrelli has been told that she’s the female Bill Nye. She replies,

“We don’t need the next Bill Nye. We need 1,000 Bill Nyes who look like the world around us”

Emily, “The Space Gal”, didn’t set out to be a science communicator. Born and raised in Appalachia, she noticed how hard her dad worked in the coal industry to provide for their family and wanted a well-paying job. So she decided to be an engineer and the first person in her family to major in STEM. In college Emily fell in love with science and the adventures it brought her. When she learned that aerospace engineering students could ride on the vomit comet if they designed science experiments accepted by NASA she chose to major in aerospace engineering. Today she holds two masters from MIT in Aerospace Engineering and in Technology and Policy, hosts TV shows, creates her own clothing line of STEM clothes geared for women and girls, and has authored several science children’s books. All her work is motivated to make science more welcoming. She identifies as a woman in STEM, first gen STEM, and being from Appalachia. All of these identities influence how she approaches empathetic science communication.

Emily says that empathetic science communication recognizes that the “things we perceive as facts are often influenced by our world view”. Emily asks us to imagine our worldviews as a makeshift house with a foundation built from our religious views and upbringing, and other deeply held beliefs such as family values and culture. When an idea threatens these pillars the brain will try to defend the house, creating the backfire effect. This psychological phenomenon states that when our core beliefs are threatened by contradictory evidence, it can actually make those original beliefs grow stronger. For example, if a person who believes the earth is flat is challenged by a photo of a spherical earth, they might believe the image is fake and they can leave the conversation believing even more strongly that the earth is flat! This may be counterintuitive to science communications who think inundating people with the facts and evidence will change their minds.

Instead, Emily advocates that the key to effective science communication is how the facts and information are delivered. These worldview houses are makeshift and can be incrementally remodeled. It just takes a lot of time and effort. She believes the key to renovating these worldview houses is empathetic science communication and shared some strategies:

1. Deliver information with kindness

She admits while this may sound obvious, it’s often easier said than done. If we speak angrily or condescendingly towards someone it can put them on the defensive and unable to think clearly. You can blame the amygdala, a small structure in the middle of your brain responsible for surviving and processing raw human emotion. Under high stress (a heated argument about the earth being flat where that person might feel defensive or embarrassed by condescending scicommers), the amygdala turns off the critical thinking part of your brain, the prefrontal cortex, and your logic and reasoning go out the window. The person is unable to think critically or carry a productive conversation.

2. Be truly empathetic

Do research beforehand to inspect their worldview to know where they’re coming from. Emily shares a personal example by discussing coal in West Virginia, where she grew up and where the coal industry is huge and provides jobs for many West Viriginians. West Virginia is also the state with the lowest percentage of people who believe in global warming. Emily wanted to understand why.

In West Virginia, coal is a love story, passed down from generation to generation. In this narrative, West Virginians are lucky to have the gift of coal and be responsible for keeping the lights on for the nation. The coal industry pays spokesmen and hosts sporting events to celebrate coal. Teachers in West Virginia are severely underpaid and are given grants to teach lessons designed by the coal industry. Children are conditioned that coal is part of their identity. These kids are taught that being environmentally friendly isn’t being friendly to West Virginians. Using the deficit model to engage with them would ignore these issues and blinds us to the corporate influence and historical and cultural contexts that shape their opinions and identities.

The coal industry is starting to dwindle as cheaper alternative energy supplants coal, and many West Virginians are laid off. So Emily spins communicating about coal as an economic issue. She points out that mountaintop removal ruins that mountain for future coal jobs and housing developments, but it can be used for solar farms, which bring in tons of long-term stable jobs. More renewable energy will lead other corporations setting up shop in the area, bringing in more jobs outside of the energy sector. Without first examining their world views, Emily wouldn’t know to appeal to West Viriginians through this economic lens.

3. “Bait the hook to suit the fish”

Focus on the interests of your audience, not what you think they should care about. One way to do this is to speak to their identity and values. She illustrated with an example of talking to someone who has conservative values about climate change (Table 1) and she highlights values typical to the two groups. To appeal to this person, talk about policies that can keep the air and water pure and clean. Point out that climate change is a national security threat. Global warming can destabilize already unstable areas where the military is operating and make those areas more dangerous. Structure talking points around the values of your audience.

| Liberal Values | Conservative Values |

| FairnessEqualityProtection from harmEmpathy | Loyalty PurityRespect for Authority Patriotism |

Finally, Emily reiterates the need for 1,000’s of Bill Nyes. She adds, “Realize you might not be the right messenger”. If you recognize you aren’t the best messenger, introduce the person you’re communicating with to someone they might relate to more, such as Katherine Hayhoe who is an evangelical christian and climate scientist or Pope Francis. On a last note, consider your final goal. Being right is easy, but changing someone’s mind is harder. Empathetic science communication can help do that.

Corey Gray on Inclusive Science Communication: Gravitational Waves and Grass Dances

Corey Grayadmits he’s a reluctant science communicator, but it’s hard to believe since he’s such an adept one. He draws on his identity as a Blackfoot and the tradition of storytelling and passing down oral histories in indigenous cultures as a science communicator. As a member of the Siksika nation, he shared that the sky and heavenly bodies are central Blackfoot culture, integrated into their stories, seasonal activities, and architecture. Corey found himself drawn to space after receiving a dual-degree in physics and applied math as an undergraduate. Now, he’s worked at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, better known as LIGO, Hanford Observatory, since 1998, as a builder, supervisor, and now the senior operations specialist.

LIGO was built to detect celestial evidence for Albert Einstein’s 1915 General Theory of Relativity, which predicted that if two black holes collided into each other they could send monumental waves through space and time. However, Einstein calculated that by the time these waves arrived at Earth they would be infinitesimal ripples, impossible to detect, since these collisions could happen extremely far from us and lightyears away.

“But that all changed”, Corey added, with LIGO, which has an extremely sensitive detector for these collisions. LIGO uses mirrors placed 4 km apart to detect minuscule changes in light, which are then converted as an electrical signal or audio signal. When mapped to sound these signals typically resemble white noise. In 2011, Corey found himself sitting at a campfire on a hike with a friend and asking how likely it would be for LIGO to actually make the detection. As Corey gazed up at the milky way his friend, a graduate student at LIGO, had statistics ready to go for detection probabilities. “Little did we know, 4 lightyears away a gravitational wave was heading towards the earth”, Corey recalls.

And then almost a century to the day after Einstein published his General Theory on Relatively the detectors chirped for the first time. Early on a September morning in 2015 a direct detection of two black holes colliding changed Corey’s life (he got a tattoo of it) and confirmed Einstein’s theory. This was the first observation of a pair of black holes and gave birth to a new field of science of Gravitational Wave Astronomy. But had to be kept a complete secret for 5 months until it was publicly announced. Corey knew he needed to share this monumental finding with the Siksika nation. After getting permission from LIGO’s head of outreach he shared the unpublished press release with his mother, Sharon Yellowfly, and she began translating it into Siksika. On February 11, 2016, the press release was published in numerous languages, including Siksika.

Corey was a middleman in the translation, he says, because he doesn’t know his own language. Federal policy mandated that indigenous children, including Corey’s mother, be separated from their families to attend residential boarding school beginning at age 5 in an attempt to strip them of their identity and prevent the Siksika language from being passed down. Despite these attempts at erasure, Sharon continues to produce translations of scientific news in Siksika. Corey and Sharon even develop new Blackfoot words together to describe LIGO discoveries.

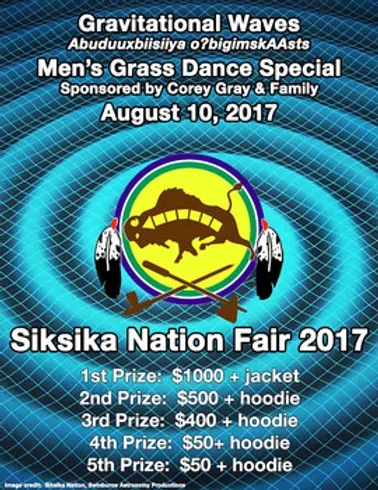

Corey has found other ways to infuse LIGO findings into his culture and increase indigenous representation in STEM. Corey sponsored a Gravitational Waves Grass Dance Special at the 2017 Siksika Nation Fair. Corey and his mom gave a talk together at an indigenous language conference. Today Corey is co-writing a science comic that takes place in Siksika Nation. As LIGO is just getting started with detecting gravitational waves, Corey is uncovering new ways to weave LIGO discoveries and his culture together, and ultimately increase science accessibility.

Each of these keynote speakers shared innovative ways they’re engaging with communities to make science more accessible and inclusive through their identities and platforms. I can’t wait to see what will be at SciCommCon 2023!

Edited by Jacqueline Goldstein

Images by Eva Rinaldi ( via flickr), kitmasterbloke, (via Wikimedia Commons), Corey Gray