Science Talk 2022 Coverage Part 1

By Kirsten Giesbrecht, edited by Jacqueline Goldstein

SciCommBites attended the Science Talk 2022 conference in March with the theme ‘Making Connections: the many arms of science communication.’ Here is part one of two summaries focusing on who are the science communicators of today.

| I’m interested in learning about the many faces of science communication and the novel ways some science communicators have found to upend traditional communication methods or media. At SciTalk I learned from scientist-artists who turn science presentations into suspense stories; marine biologists who podcast Dungeons and Dragons spinoff games; members of the LGBTQIA+ community who are trailblazing authors, innovative mentors, and students who merge art and science; compassionate speakers; and early-career scientists who publish policies. |

Dugongs and Sea Dragons

If you like marine biology and the tabletop role-playing game, Dungeons and Dragons, I have the perfect podcast recommendation for you. Dugongs and Sea Dragons is a live tabletop role-playing podcast where players go on adventures that are marine biology or conservation-themed, incorporating marine biology, fantasy, conservation, and tabletop role-playing games. All of the current members are marine biologists and scientists, and they pepper scientific easter eggs throughout each podcast. If you listen to their podcast and find an easter egg you could win game dice!

In the session, listeners followed the characters to a calm coastal resort town where they investigated the disappearance of the resort’s cook leading them on an adventure that included learning about sustainable indigenous clam gardening of the Salish sea. This is a great medium for learning about marine biology and conservation and is very entertaining!

Dugongs and Sea Dragons has been among the top twenty in natural science podcasts in the US many times and top 10 podcasts in several other countries. You can listen to this podcast wherever you get your podcast (including Apple podcasts and Spotify). You can follow them on Twitter at @DugongsD or support them on Patreon!

Queer Science Communicators Panel

After attending Science Talk previously, Tzula Propp (they/them) and Annie Wentz (she/they) were inspired to organize this panel as a dedicated space for queer science communicators. The panel of three included queer science communicators at various stages in their careers. The first panelist, Dr. Antentor ‘AJ’ Hinton (he/him), is an Assistant Professor at Vanderbilt University in molecular physiology and biophysics. Dr. Hinton spoke about how we do our best work when we can be our true selves and his method of cultivating a lab environment to help trainees thrive.

Dr. Hinton believes in an anti-extractive, holistic approach to mentoring his students. He’s written about mentoring, reimagining the STEM pipeline, and developing cultural humility in mentoring. Dr. Hinton asks his students to take an emotional intelligence test and a love language test to best understand how that student can succeed and learn. The group takes enrichment Fridays to help members in the lab have the best chance of succeeding when they are facing hardships or under acute stress, like a fellowship deadline or family crisis. Together they brainstorm how to restructure that member’s load. The lab has a mental health professional available as a resource. Dr. Hinton wants his trainees to flourish as both scientists and as individuals.

The second panelist, Grace Deitzler (she/her/they/them) is a graduate student at Oregon State University, who hosts a radio show and started an art and science club at OSU. She shared how she connects art to science and to exploring our authentic selves. Grace decided to start this art and science group Seminarium– meaning to sow the seeds of knowledge – after attending an inspiring talk given by mathematician and sculptor, Michael Schultheis. Together faculty and graduate students in science and art departments founded the group. You can view their recent events here.

Through Seminarium, Grace has reconsidered how we view the relationship between science and art. Typically we think of art as a vehicle to communicate science and being in service to science. But Grace challenged us to consider that art is more than just for consumption; art and creativity are ways to build strong and meaningful relationships and community. Art can create networks independent of its usefulness in communicating science. View art as a ‘relational process’ and art can be used as a way to explore our identities and our authentic selves.

The third panelist, Dr. Tara Roberson (she/her) is a post-doctoral research fellow who is publishing a book about queer science communication. Towards the end of her PhD, she realized that there was a very active, but not visible queer science community involved in drag, art, and gallery showings. However, Dr. Roberson noticed there was a gap between what she was experiencing and what was reflected in the science communication research journals or books. So, she and her colleague wrote about it in a special issue of the Journal of Science Communication.

Her upcoming book is a collection of research chapters, with over 40 contributors from across the globe, of different areas of queer science communication, including trans health, queer coding in science fiction, and how queer-related rhetoric is used in science communication tools and tactics. She hopes the book is the start of a conversation and that more publications will come about in reaction to her book.

The panel also spoke about the role of allies in queer science communication. Tzula suggested that those who identify as allies reconsider their roles to be accomplices, rather than allies, to marginalized folks and work hard to prevent harm from coming to LGBTQIA+ individuals. Other panelists agreed, adding that accomplices should educate themselves so they can have more authentic conversations with members of the LGBTQIA+ community.

On a final note, the panelists reflected on the future of queer science communication. The panelists suggested that when queer science communicators trailblaze or make space, they should advocate that their work be recognized as an essential role or a paid position.

Compassionate Science Communication in Practice

This virtual workshop was hosted by Dr. Jennifer Ma Ph.D., founder of Gentle Facts; an evidence-based compassionate science communication Instagram account with information about global health crises such as Covid-19 and global warming. She emphasized when communicating with your audience about a science topic to have their perspectives and cares at the forefront of your view. She defines compassionate science communication as:

- Understanding your audience and what they care about

- Identifying and validating their needs and values and their concerns or negative emotions they have about a topic ( i.e. distrust in the safety or efficacy of vaccines, hopelessness that their daily actions don’t impact climate change, health concerns over GMO foods)

- Helping them by providing relevant scientific information

- You can provide reliable information addressing their needs and directly address misinformation to relieve uncertainty and anxiety ( i.e how to best protect their family during a pandemic)

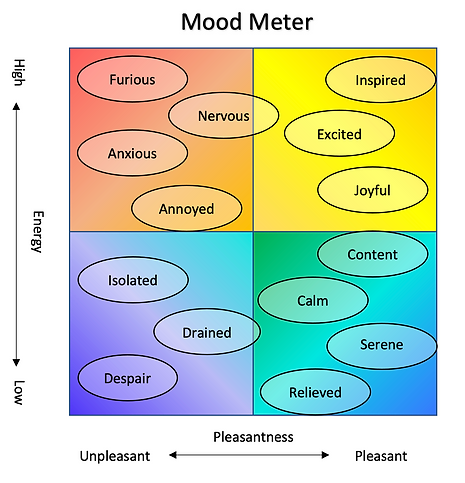

Another aspect of compassionate science communication is identifying where your audience currently is emotionally and using your conversation to influence their emotions. An exercise you can try for yourself is assessing what emotions you think your audience might be feeling and knowing how you want to shift that emotion. A useful visualization is the Mood Meter, developed by Marc Brackket PhD at the Yale Center on Emotional Intelligence. You can imagine moods falling on a plane with pleasantness increasing from left to right and the energy from bottom to top. An inspired mood would fall in the upper right of the mood meter where energy and pleasantness are both high. A furious mood would lie in the upper left where pleasantness is low but energy is high.

You can imagine how your audience is currently feeling, which direction you would like to shift their mood, and how the energy and pleasantness would need to change for your audience to land on that desired emotion. However, Dr. Ma reminds the audience that compassionate science communication is not manipulating your audience’s emotions to convince them to do something that you think is best for them, since we don’t know what is best for the audience. Rather, compassionate science communication is placing your audience first and understanding how to complement and respect their values and needs. For instance, understanding the values of your audience can help you address their concerns over topics such as climate change and vaccination efficacy and safety.

Dr. Ma breaks down compassionate science communication into four steps to move your audience to a better emotional place:

- Listen

- This may sound simple, but this step can require the most energy. Although you may want to jump in with our thoughts and problem solve, listen to your audience’s concerns to better understand and validate them. Invite your audience to share why they are feeling a specific way about a topic.

- Stay open-minded, listen without judgment, and pay attention to both your audience’s emotions and your own emotions and biases.

- Appreciate your audience’s willingness to share and tell them that!

2. Relate

- Identify something you and your audience have in common. This helps you empathize and share a true connection with your audience.

3. Inform

- Make it very clear how the information you share with your audience is relevant and keep your thought process and your sources of information transparent to build trust..( i.e. you are very worried about your family’s health, vaccination is extremely important and can lower your risk of passing the illness to your kids). Be respectful.

4. Encourage

- Give a positive spin to the suggestions or information that you share with your audience. For example, if discussing avoiding meat in diets, tell your audience about flavorful plant-based recipes they can try. Remind them how influential one person can be and how their peers will pay attention to their actions. Move their emotions towards the right on the mood meter.

Dr. Ma reminds us to also be compassionate to ourselves. It is okay to set boundaries or step away if your audience is not open to the conversation. Resting and reenergizing yourself is a critical step to practicing compassionate science communication and connecting with your audience while being your genuine self!

Science Policy Workshop

This workshop was hosted by a panel of previously accepted authors of theJournal of Science Policy and Governance (JSPG) including Andrew Cain and Kaylee Henry. The authors presented an introductory guide to science policy writing for early-career scientists and worked with attendees to develop an example science policy outline.

The panel emphasized differences between science policy writing and science journal writing. For instance, science paper writing is objective and interprets results. Policy writing on the other hand draws from, at times, sparse evidence on emerging issues or on well-researched topics that require multiple expertises’ perspectives, or else there would be no need to write a recommendation. Additionally, the policy suggestions need to appeal to a wide audience with various backgrounds and values. A policy developed using strictly moral arguments is not likely to be effective. Instead, effective policies rely on multiple perspectives, such as an economic perspective, that appeal to a wide array of policymakers.

The journal JSPG has multiple calls throughout the year for specific topics and exclusively publishes early-career scientists, including graduate students. The journal also hosts several free writing workshops throughout the year. If you are interested in dipping your toes into science policy writing you should consider submitting a paper to JSPG!

Storyform Science

The Storyform Science workshop was hosted by its founder Holly Walter Kerby, chemistry professor and playwright; and H. Adam Steinburg, ArtForScience founder, and Storyform Instructor. Holly created Storyform Science from her desire to teach chemistry to all ages and any audience. Together Holly and Adam use the Storyform Science method to teach a variety of science communication products such as crafting engaging presentations or creating Storygraphics, Adam’s twist on an infographic.

Holly pointed out that the default way people decipher their world is to turn it into a narrative. The Storyform Science method is a way to create presentations and visuals designed to maximize audience attention and learning by turning the science presentation into a suspenseful narrative. Holly uses this Storyform Storyboard presentation template for her students to craft their narratives. However, she notes that the Storyform Science method does not involve a personal narrative, such as Moth or a TED talk. Participants of the workshop practiced filling out the storyboard template of their own research. Instead of using text to fill out the storyboard, participants drew icons related to their research. According to Holly, icons reduce jargon, are easy to revise, and are a better form of communication compared to text. Icons could be doodles symbolizing both physical items and non-physical concepts such as places, tools, people, data, or ideas. Icons used in the storyboard could also be used to make storygraphics.

Adam led the workshop portion on constructing storygraphics and engaging visuals. Storygraphics are infographics that tell a story, are built on the same principle of constructing narratives from your data and research, and have a similar template to the presentation storyboard templates. To construct the visuals in a Storygraphic, Adam suggests selecting icons, expanding them, and adding key phrases to create the main images. Storygraphics can be used as part of a poster or even as an entire poster.

Perhaps the most critical aspect of constructing an effective Storyform Science presentation or storygraphic is receiving feedback and critiques on it. In Storyform Science courses, students will present in a variety of locations, from coffee shops to corn mazes, and receive feedback from a broad array of audiences. Their students will also use feedback rubrics for presentations and storygraphics to critique each other and receive constructive criticism. Both Holly and Adam emphasized multiple times throughout the workshop that feedback is absolutely crucial to successful Storyform Science products.

If you are interested in learning more about Storyform Science or getting involved, you can register for their 6-week summer zoom course or you can be a beta tester for their new workshop video series. The workshop was an exciting glimpse into how framing your research through a narrative lens can draw your audience in and leave them with a greater understanding of your research compared to traditional science presentation methods.

Final thoughts

These panels and workshops demonstrated that science communicators are artists, authors, mentors, empathizers, game enthusiasts, and policy writers. These science communicators are constantly finding new ways to reach and connect with audiences. Part two of coverage will be coming out shortly!

Dugongs and Sea Dragon original cover art by Ethan Kocak (@Blackmudpuppy) use granted by https://dugongsandseadragons.weebly.com/.

Figures used under CC-BY-SA-4.0 and CC BY-SA 3.0.