Science Talk 2022 Coverage Part 2

By Teodora Stoica

SciCommBites attended the Science Talk 2022 conference in March with the theme ‘Making Connections: the many arms of science communication.’ Here is the final part of the summaries focusing on how to create science communication and community online.

| My science communication expertise lies primarily in writing, and I wanted to take a closer look at how storytelling can be applied to other mediums like the creation of a science video. Since the pandemic highlighted the drastic need for science communication as a skill for doctors and scientists, I was interested in learning efficient ways of teaching scicomm to these populations. There was no shortage of invaluable resources for creating, applying, and enhancing science communication at this year’s Science Talk. I was also made aware that by only taking into account our own interests as scicommers, we often miss how people can apply scientific research in their daily lives, so ways to engage the community is an often overlooked part of science communication. All these issues were masterfully tackled by science communication experts. Here are the key takeaways:Creating an engaging video about science is not intimidating with the right resourcesEffective SciComm is essential to propel research forward and to widen any scientists’ reachTaking into account community needs is paramount to actionable scicomm |

How to create an engaging video about science

In this workshop, novices in creating online videos, like me, learned how to create a two-minute whiteboard style video about a scientific concept or project. Dr. Lisa Dennison, Director of Research Development Communications at UT Southwestern Medical Center and Co-director of Science Sketches, led a nuts-and-bolts tutorial about how to record and edit science videos that can reach a broad audience. Lisa was supportive in encouraging us that no fancy equipment is necessary and anyone can do this by simply following a recipe!

Here are the ingredients:

- Write a short 250 word script

- De-jargonize the script

- Create a storyboard and draw it out

- Film it

- Add audio

- Edit it

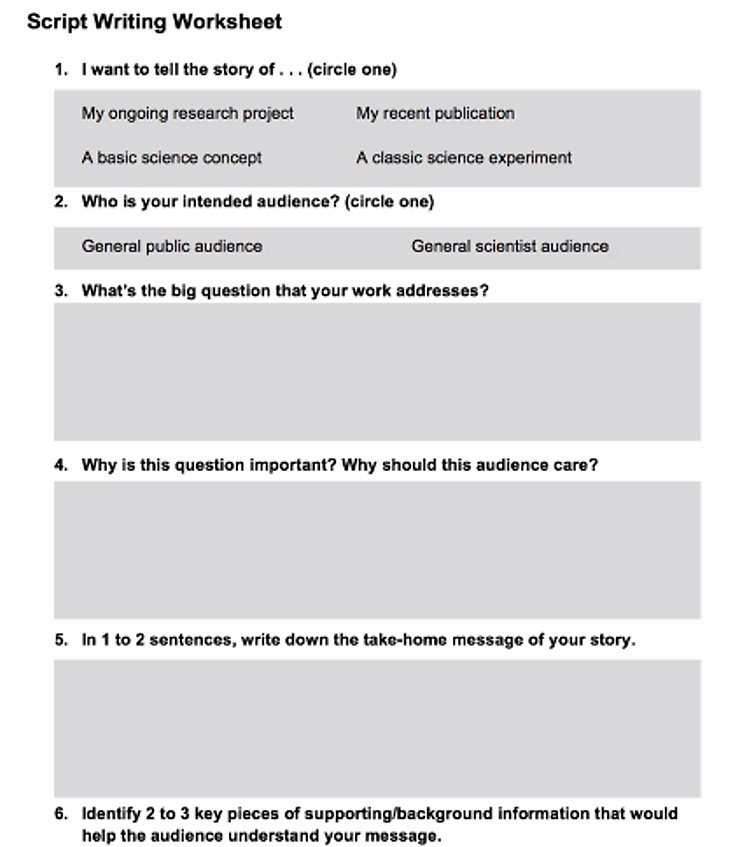

The workshop provided an easy to follow worksheet to facilitate the writing of this short script.

The script is very short, so every word and sentence counts. After writing an initial draft, make sure you get feedback from a friend representative of your audience. If they don’t understand it, go back to step 2 and simplify your language using the De-jargonizer.

I wasn’t intimidated so far, but was very nervous about the next step: creating illustrations. The point here is not to create great art but to create simple art to explain tricky scientific concepts. It’s important that everything in the script is illustrated, because when adding audio later, there will be dead space if no written keyword or image is tied to the concept. I learned it doesn’t matter how long it takes to draw something, because during editing, the speed of the audio will match that of the illustration.

The next step is to create a storyboard, and to think through how many sheets you will need. Something I never thought about is that the words and illustrations should be large enough to fit on a smartphone, since this content will be posted to YouTube. The guides below show how big the text should be, and encourage the creator to use different colored pens to bring the story together.

Next, we can record the audio (in a very quiet environment!) using anything as simple as the Iphone memo app, and send the file to yourself. Recording the video is also easy. Secure a camera phone (using a tripod or lab clamp) and point it towards the piece of paper on the table, press record and start drawing! It’s important to go through the script or audio line-by-line as you draw to make sure everything is drawn in exactly the same order that you say it. The final product will feature just the narrator’s voice and a timelapse of all the drawings.

The last part is editing the video, and Science Sketches provides a quick tutorial. There are several software packages that are not only easy, but fun to use, such as iMovie or Windows Movie Maker.

Finally, you can submit your video to submit@sciencesketches.org and the team will guide you through the submission process. For a detailed step-by-step guide, Lisa provided a free resource here, and encouraged us to reach out with questions by emailing info@sciencesketches.org.

Helping scientists maximize impact with SciComm

Science communication is an essential tool in a doctor or scientist’s toolkit, but it is not one that is typically taught in their training. This compelling workshop highlighted the importance of scicomm and ways it can be incorporated into teaching activities. Nidhi Parekh, Founder and Lead Writer of The Shared Microscope, outlined why storytelling as communication is such an important part of scicomm: it humanizes the scientific process and makes technical knowledge easy-to-understand. It’s hard for the general public to see scientists as anything other than scientists, so empathizing with scientists’ mistakes and failures makes it easier for the public to internalize the scientific information.

Through (another!) easy to follow recipe, Nidhi explained how to make SciComm more impactful. The first ingredient is to identify the purpose. That is – what is the response you wish to elicit from your audience? Do you wish to educate, build awareness or simply intrigue the audience? Do you want to start a conversation or spark a debate? It’s important to keep in mind the platform you’re using – the message may be received differently on Twitter vs. YouTube.

The second ingredient – keep your audience in mind and be mindful of culture, identity and accessibility. A great example used to illustrate this point is the Life Saving Dot campaign. Partnering up with medical foundations, the advertising company Grey Group Singapore partnered with medical groups to develop an iodine patch in the form of a bindi, targeting Indian women that suffer from diseases due to iodine efficiency. The women could get their daily dose of iodine without having to change their behavior. The video they created was not only informative, but clear and memorable, which is the third ingredient in making scicomm more impactful.

Sheeva Azma, a scientist turned science writer, communications strategist and journalist, continued the informative discussion by folding in a real world example: the pandemic. Science communication during the pandemic was fraught with misinformation. She emphasized that there really is only one rule to effective scicomm, especially during the pandemic: know your audience, what they know, and what they value. Examples of effective pandemic scicomm included not taking a specific political viewpoint, critically analyzing the facts and perhaps most important – communicating nonjudgmentally in a way that doesn’t shame or scare people. The application of these strategies was apparent in the Unbiased Science podcast, the NY Times vaccine explainers, the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health’s Instagram and Katherine Wu’s articles, among others.

It’s important to pause and remember that scicomm is a unique form of communication style. Unlike the political news cycle that is about garnering constituent support and doesn’t always have to be 100% factual, scicomm is based on factual accuracy, critical thinking skills and is the antithesis of the immediate gratification culture. Therefore knowing your audience, appealing to shared values (like staying healthy and moving past the pandemic), and appealing to your friends and family first is paramount. By engaging your closest sources, you begin a snowball effect that can have tremendous impact when they share easy-to-understand scientific facts with their respective networks.

Applied science communication

Why do we scicomm? For the majority, it’s because we have an interest in a science topic, and we want the general public to know. Why do we want the general public to know? Because we want them to apply the information to their daily lives. But what if the general public doesn’t want or know how? This workshop highlighted the importance of crafting scicomm messages from community needs, so they can become relevant, actionable and practical.

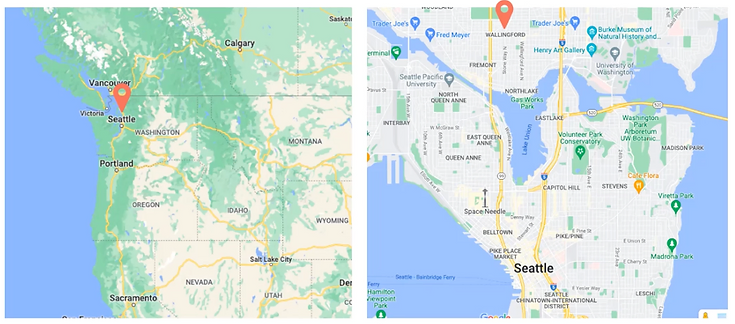

Amelia Bachelda, Director of Outreach and Education at the University of Washington Institute for Learning and Brain Sciences, began the discussion with a simple example. Say someone asks where you’re from, and you say Seattle. You realize the person knows Seattle well, and you adjust your message to be specific enough for them to understand (Wallingford). In the same way, crafting an effective scicomm message is shifting the scale of what you need to say to be relevant and useful at the same time, while also taking into account the audience’s prior experiences.

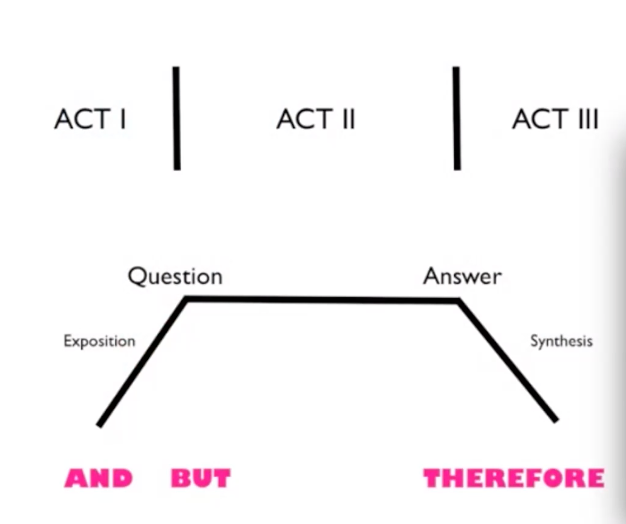

Crafting an effective message begins with great storytelling. Randy Olson, the marine biologist turned filmmaker, explains in his TED talk that persuasive storytelling has three parts: beginning, middle and end. As trained scientists, we usually spend far too much time in the beginning of a story describing the background (or exposition). Think of the last scientific talk you attended and the lengthy explanation of the scientific query: “This molecule does this and this molecule does this and we think this set of molecules do this and…”. The story stagnates before it even starts. Instead, Randy encourages us to transition between each act of our story, starting with the exposition (using and), introducing a problem (using but) and describing a consequence (using therefore; see below).In this way, the story becomes compelling, “This molecule does this and this, but this molecule also does that, therefore we did this experiment and found out this amazing thing you need to know!”

The workshop continued when Marley Jarvis, Outreach and Education Specialist at the University of Washington Institute for Learning and Brain Sciences, provided a great explanation of the different pieces that constitute Perspective – that is, the cultural frame in which you bring your message – using a useful visual (see below).

When crafting a scicomm message, the puzzle pieces above can ensure that community needs are being sensitively considered. To better understand, here are examples of a few of them. Harking back to our previous geographic example:

- Prior knowledge asks: What assumptions is the scientist making about the importance of science? We don’t always make data-driven decisions so how can we fold that into our message to the general public?

- Purpose asks, What is the main message and the intended or possible impacts of sharing it? Am I the right person to share it? So often we forget that we are not alone in our scicomm pursuits, and

- Partners reminds us to engage in reciprocal partnerships with other vibrant communities and organizations.

For those interested in creating a public engagement project using these and other useful scicomm tools, the Institute for Learning and Brain Sciences has developed a free framework to get you started.

Summary

These three “how-to” workshops delved deep into ways to make scicomm more effective, from great storytelling strategies, to creating videos and making sure to incorporate the community’s needs into your messages. There is still much to learn about improving the scientific message to the public, but this is a fantastic start.

Creating Community Online

Moderated by Elizabeth Bojsza, Graduate Program Director at the Alda Center for Communicating Science, this panel discussed challenges in communicating science online and best practices to address them. Josh Rice, who is a Lecturer in Applied Improvisation and Alda-Certified Instructor along with Claire Holesovsky, a Science Communication Specialist, began the discussion with a simple question:

How does the mindset of a virtual audience differ from one in person?

Since the beginning of the pandemic when the majority of learning content was pivoted online, science communicators had to address several challenges of how to best deliver important messages to online audiences. For example, paying attention in class all day is not the same as paying attention online all day. Zoom fatigue is real. Two ways to address this are encouraging your audience to participate in fun activities throughout the session, as well as providing some time for reflection. This can be applied both to a broad range of scicomm styles, including writing, videography and especially podcasts.

Beginning a project on any online communication platform can be a daunting task. The panelists reminded us that the most important step is to simply ask your audience – what content do you engage with most? Creating a survey and sending it to partners in the scicomm community can be helpful in addressing what the audience needs instead of retrofitting the content later. Depending on the goal of your project, the platform you use is also critical. For example, if the audience is high-schoolers and the format is visual, perhaps Instagram (and not Facebook) would be a great option. At the start, being mindful of audience needs is crucial. Setting expectations about how much content to engage in, establishing a clear set of community guidelines, and making sure transparency is a key value of your project will help grow your community. A great example given by the panelists is Emily Adkin, a climate journalist and author of the “Heated” newsletter. Emily always gives the readers a snippet of where her emotions are, which provides a window into who she is; something that isn’t always visibible online. That kind of vulnerability is pivotal in building community online. They also encouraged us not to shy away from salesmanship techniques and remind participants of the benefit of their voluntary involvement and enthusiasm.

The panelists ended with a reminder to tap all your science communication resources (we are a large community after all!), so we’re not the only ones creating the content in order to amplify the scicomm message. Finally, for those who need more resources on this salient topic, they provided an indispensable list of resources.

Summary

Anyone communicating science online should take time to get to know their audience, and be mindful of their needs. This will dictate the content and best online platform to use for the most effective scicomm.

Edited by Jacqueline Goldstein