SciPEP 2023 Part 4: Turning Insights about Basic Science Communication into Action

SciCommBites X SciPEP collaboration: This SciCommBites summary is the fourth and last in our coverage of the two day SciPEP conference.

TL;DR

- There are many ideas, opportunities, and entry points to contribute to a collective understanding about basic science communication.

- Trainers need to develop the skills to connect core training content to each trainee, rather than design content around differences in type or focus of research.

- Reframing relevance as connection enables communicators to become more strategically responsive to values, interests, and questions of different publics.

- More mechanisms that encourage collaborations and co-creation of projects would help develop and advance basic science communication research and practice specifically, and the broad science communication ecosystem generally.

- Visual organization tools could help the science communication community identify key research questions as well as map out needed information about the goals, objectives, and tactics for basic science communication.

The Background

Day 1 of SciPEP 2023 explored new insights and findings based on research and expertise in the context of basic science communication. The main questions focused on the extent to which basic science communication may require unique strategies and tactics that are different from those of applied science.

In our prior coverage (here, and here), we learned about:

- public identities and views of basic science,

- basic scientists’ identities and views on science and communication,

- how publics’ and scientists’ views converge and diverge,

- new insights on future directions for basic science communication research, and

- reframing and broadening “relevance” in science communication as establishing connections with different publics instead of just the “utility of” basic science.

On Day 2 of SciPEP, leaders from The Kavli Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science, along with invited expert guests, convened to discuss how to turn insights about basic science communication into new ideas and plans for action. In their welcome video, Cynthia Friend, President of The Kavli Foundation, and Asmeret Asefaw Berhe, Director of the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science (DOE) emphasized a shared interest in strengthening the relationship between science and society and their hope that SciPEP would inspire new social science research and intentionality and innovation between basic science and publics for years to come. Keegan Sawyer (DOE Office of Science), added that it is important for the science communication community to work together to generate ideas, forge partnerships or collaborations, and catalyze opportunities for taking action.

Charting A Pathway From Insights To Action

In this session, Rose Hendricks (Association of Science and Technology Centers) presented the results of a qualitative research study (Hendricks and Fond, 2023) to understand the science communication community’s perspective on priorities for basic science communication and engagement. After Hendrick’s presentation, the study results were discussed by a panel composed of Ashley Cate (University of Wisconsin- Madison), Xinnan Du (Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology), and Reyhaneh Maktoufi (HHMI Tangled Bank Studios). The session was facilitated by Keegan Sawyer.

The starting point for the study, said Hendricks, is Charting a Path for Public Engagement in Basic Science: A Prospectus (SciPEP 2022). The SciPEP prospectus outlines major open questions about basic science communication and a simple framework for taking action: champion quality evidence, catalyze conversations, and connect people and institutions. The prospectus emphasizes that there are many more questions about basic science communication than answers and calls for a comprehensive research agenda.

The study by Hendricks and Fond is one step toward developing a comprehensive research agenda. They conducted semi-structured interviews with 30 practitioners, researchers, and scientists to explore their views on what is essential to know first about basic science communication and what kinds of activities, research or otherwise, will help the community pursue answers. Hendricks and Fond observed that participants raised many similar questions to one another and to the questions raised in the SciPEP prospectus. Most participants found it quite challenging to answer what the field should do to address the open questions, said Hendricks.

Hendricks described several overarching themes in participants’ responses that contribute to the challenge:

- A need for detailed and context-specific information about basic science communication. For example, when considering what information is needed to address the question “How do members of the public think about basic science?,” participants wanted to know “Who are the specific publics?” and “What are their past experiences with basic science and engagement?

- An uncertainty about whether and when ‘basic science’ is a helpful focal point (Figure 1).“Under which circumstances is a distinction between basic and applied science the most helpful? When might other distinctions, or no distinctions at all, be most helpful?

- A tendency to associate basic science only with one-way communication. Participants who discussed multi-directional engagement only provided applied science examples.

However, a number of participants did have some ideas for how the questions they saw as most important could be addressed. Drawing from their own expertise as social scientists, Hendricks and Fond synthesized the participant’s responses into six priority questions:

- What are the values that guide basic science communication and engagement?

- What do we know about audience perspectives on basic science topics?

- What is the role of training in catalyzing effective and equitable basic science communication and engagement?

- What goals do communicators have for sharing basic science with public audiences, and what goals are strategic?

- How should various, basic science topics be framed in different contexts to achieve particular goals?

- What outcomes are possible and common, and what can the field learn about evaluation practices that are meaningful and realistic?

Hendricks emphasized that these questions are just a starting point. “The good news,” said Hendricks, “is that there are many opportunities and entry points to contribute to a collective understanding,” such as field-wide discussions, evaluation, and combined qualitative and quantitative research approaches.

To begin the discussion, Sawyer asked the panelists what, if anything, surprised them about the interview responses. Maktoufi highlighted that strategic thinking showed up in all the responses. She said this is notable because often science communication organizations do not prioritize asking strategic questions when developing their communications. Maktoufi also asked if it is “helpful for us to have so many dichotomies.” For example, we have this idea of Western Science, and we have traditional science, and those are not actually two separate things. Cate emphasized that determining whether the distinction between basic and applied science is harmful or helpful may come down to the specific audiences for science communication and engagement endeavors.

When asked how the panelists would get started to advance basic science communication, Du stressed the need for evaluation. Her team worked with evaluators to help clarify their strategic goals and identify specific tactics to achieve those goals. Cate saw a need to deepen understanding of how researchers are segmenting audiences and where there are opportunities for relationship building. Maktoufi suggested starting with funding experimental spaces where communicators have the freedom to try different things without facing penalties for failure.

| What we learned:There are more questions about basic science communication than there are answers. Issues that make it challenging to determine how to address open questions in basic science communication include:a need for detailed and context-specific information;uncertainty about whether and when ‘basic science’ is a helpful focal point; and a tendency to associate basic science with one-way communication.There are many ideas, opportunities, and entry points to contribute to a collective understanding about basic science communication. |

Sci Comm Training: What do we need?

Are existing approaches to communication training effective for basic science communication? What do scientists who identify as doing more basic research need? What, if anything, needs to be different so that scientists or other professionals who communicate in the context of basic research are as effective as possible? In the second session of Day 2, an expert panel explored these questions, and more, through the following three lenses: communication goals, relevance as connection, and core competencies. The expert panel included Laura Lindenfeld (Stony Brook University and the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science), Anthony Dudo (the University of Texas at Austin), Claudia Fracchiolla (American Physical Society), and Bruce Lewenstein (Cornell University). Brooke Smith (The Kavli Foundation) facilitated the discussion.

Scientists’ Communication Goals

To set the stage, Dudo shared key insights about scientists and science communication training from social science research. First, scientists often approach communication with a narrow view, one that is primarily focused on tactics, while they should be focused on setting strategic goals. Second, the knowledge deficit model tends to be a default assumption of many scientists. Last, these trends are not unique to scientists. Science communication training curricula also tend to focus on tactics, such as how to use social media and how to reduce jargon, rather than strategic communications, developing clear communication goals and audiences.

Do training efforts need to be designed around the difference between basic and applied researchers? “Not really,” answered Dudo. Rather, training requires comprehensive learning objectives and curricula that center the trainees and their individual journeys through the training process, generally. That means trainers need to develop the skills to connect core training content to each trainee, rather than design content around differences in type or focus of research.

Relevance

Reframing relevance as connection resonated with both Lindenfeld and Fracchiolla. Their programs focus specifically on how trainees are learning to connect with and understand their audiences. Lindenfeld emphasized the need to be strategically responsive to society’s questions around where better science communication and engagement is needed. The science communication training provided by the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science encourages scientists to ask themselves the question “Who am I connecting with?” before and during engagement so they can remain “relevant and responsive” to an audience’s needs.

Fracchiolla works on the Science Trust Project, which trains physicists to address misinformation in science by focusing on “reflective listening, understanding people’s identities, and how to engage in those conversations.” These skills are essential, as understanding peoples’ identities is the first step to building trust.” Lewenstein added that trust takes time, often years, and it is essential to include this as a part of scicomm trainings.

Core competencies

Rather than identify core competencies needed for effective science communication, the panel explored how to effectively teach core competencies. First, Lewenstein summarized his paper, How should we organize science communication trainings to achieve competencies? (Lewenstein and Baram-Tsabari, 2022). This paper points out that there are different scales of science communication learners – occasional (new or sporadic science communicators), active (e.g., people who incorporate science communication into their jobs) and professional (science communication is their job). He also points out that science communication trainers are not well versed in educational theory. For example, educational theory supports use of learning progressions – the idea that people need to revisit what they’ve learned before. This calls into question whether “one-off trainings” are appropriate for scientists to learn core competencies, such as reflective listening. When scientists participate in longer-term programs that integrate experiential learning programs, they can practice and perform what they are learning over time, which is more impactful.

Does this mean that all one-off science communication training is ineffective? Dudo said there likely needs to be different types of training to achieve different types of goals. Lindenfeld expressed a need for a broad map of the science communication training to better understand the gaps (e.g., strategic communications training vs tactical/skills-focused training), explore what is or is not working, and examine “how we can do better so we can hold ourselves accountable to high standards.”

Lewenstein also said science communication training needs to incorporate theories from STS (science and technology studies) and the history and sociology of science. STS theory tells us that asking whether “basic science” requires distinct consideration from “applied science” is the wrong question, because the same work can be both basic and applied. In other words, distinctions between basic and applied are most meaningful in very particular contexts, such as to the scientists who carry out the work or in science communication efforts to acquire more research funding.

| What we learned:Trainers need to develop the skills to connect core training content to each trainee, rather than design content around differences in type or focus of research. Reframing relevance as connection enables communicators to become more strategically responsive to values, interests, and questions of different publics. Science communication training of core competencies would benefit from educational theory, STS theory, and the history and sociology of science. |

A SciComm Research Agenda – What do we include?

When SciPEP first began, The Kavli Foundation commissioned a survey of the literature to determine the state of scholarship on communicating basic science and found “troubling little,” said Rick Borchelt (DOE Office of Science). Borchelt explained that the topic of this session, thus, is to explore “what questions we wish had been asked or what could be asked now, to help further our understanding of how scientists can productively engage various publics in the context of basic science.” The conversation was initially framed by Sara Yeo (University of Utah) and Matt VanDyke (University of Alabama). After their framing remarks, Nic Bennett, (University of Texas at Austin) and Jayatri Das (Franklin Institute Science Museum) joined in the discussion.

How do we think about what to include in a research agenda to advance basic science communication?

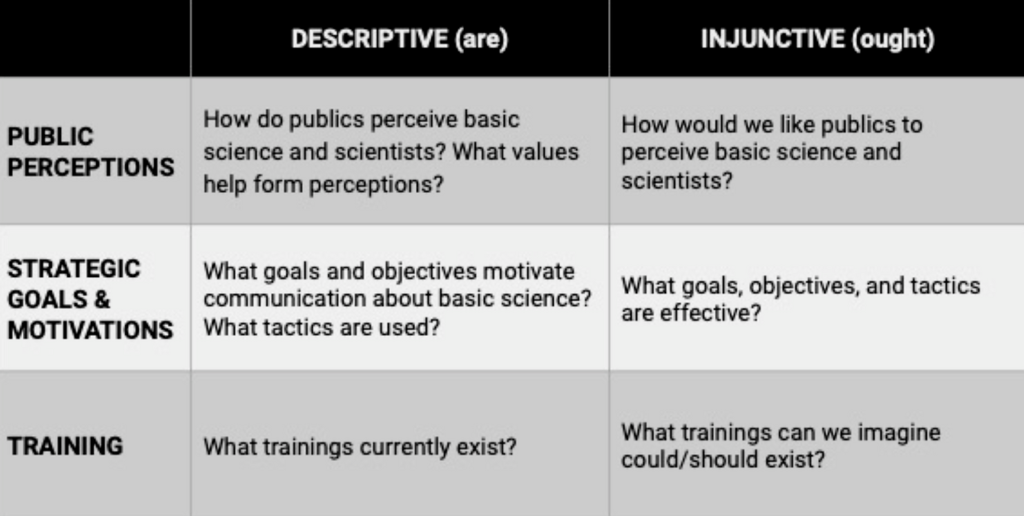

Yeo described two approaches that could help the science communication community identify key research questions as well as map out needed information about the goals, objectives and the tactics for basic science communication, and science more generally (Table 1). First, she recounted three broad topical areas where we have unanswered questions: public perceptions of science, scientists’ strategic goals and motivations, and training. She posited that what we want to know about each of these topics can be divided into descriptive (what “are”) questions and injunctive (what “could be” or “ought to be”) questions.

Second, Yeo shared an “organizing tool for thinking about goals, objectives, and the tactics” in basic science communication training (Figure 2). Each training objective in this pie chart could be related to the different types of science communication learners described in the 2022 Lewenstein and Baram-Tsabari paper. Each specific communication goal, “a slice of the pie,” may have different objectives depending on the level of practice of the learner (science communicator). Yeo further explained that tactics, which are not illustrated, can be considered the “Communication 101” or relevant core competencies for science communication goals and objectives.

What information and expertise can help inform the development of a research agenda?

VanDyke emphasized the need to think more broadly about three areas in conversations about a research agenda for basic science communication: evidence, professions, and institutions.

Evidence that provides relevant insights on communication strategies may already exist. VanDyke, a public relations scholar, stressed that fields such as media psychology, public relations, and organizational and institutional communication are overlooked yet important, existing bodies of knowledge. These fields can inform communication strategies and new research questions. For example, more than a decade of research in positive media psychology has explored “how media can inspire or promote a sense of elevation” in audiences. This body of knowledge can inform conversations about how basic science communication produced awe or a sense of wonder.

Consider a broader range of professions and/or professionals who should be included in the science communication ecosystem. What would it look like for public information officers, public affairs officers, or extension professionals to support basic science communication?

Look at the values, definitions, and processes of organizations and institutions who support (or should support) science communication. Are their communication functions centralized or decentralized? Depending on how communication is organized, what are the implications for public engagement?

Advancing and Prioritizing Research Ideas

In response to Yeo’s and VanDyke’s framing remarks, Bennet asked “who gets to decide what the ‘aughts’ are? … and how to actively resist reproducing systems of oppression in science communication. VanDyke suggested looking at collective partnerships and institutions, who “drive a lot of what at least the field does in terms of individual research.” Additionally, institutions are not acknowledging or valuing this work ‘when it comes time for tenure and promotion.’ Das, on the other hand, looked beyond individual institutions and asked, “how do we elevate the importance of sci comm to a disciplinary level, where it’s not reliant on an individual institution or scientists to determine the value of science communication?”

Bennet pointed out “the reason we keep calling for interdisciplinarity” is that the norms science communication research and practice systems are rewarding us for staying siloed. Borchelt agreed. “There is a great disconnect between the people who are doing this work and the people who are doing the research on this work.” How can we bring these two parties, interested in such similar goals and outcomes, closer together? Das added that a huge barrier for many practitioners is access to the literature. Many journals are not open access and practitioners may not have access through their institution the way academics do. Van Dyke suggested a stronger role for professional associations, as they can often be doing much of the professional development in an area.

Yeo emphasized the need for incentives to collaborate and form multidisciplinary teams. She shared the example of Advancing Informal STEM Learning (AISL), a program funded by the National Science Foundation, that requires practitioners and researchers to collaborate. She said that more mechanisms that encourage collaborations and co-creation of projects would help all science communication research and practice, not just basic science or basic scientists.

Borchelt wrapped up by asking the panelists to share a major research question that they would like a basic science communication research agenda to address.

- Bennet: “Who is included and given power with the ways that we currently do science communication, and what are the interventions we can do to change that?”

- VanDyke: “How can we integrate the existing communication subdomains and knowledge bases to better inform and complement some of the questions we’re asking?”

- Yeo: Research on effective tactics. “There’s an increasing recognition that evaluation is a necessary part of public communication and/or engagement.”

- Das: How to shift from knowledge deficit thinking to an engagement, collaboration, dialogue mindset.

| What we learned:Visual organization tools could help the science communication community identify key research questions as well as map out needed information about the goals, objectives and the tactics for basic science communication.A broader range of evidence, professional expertise, and institutional considerations will be important to inform communication strategies and new research questions.More mechanisms that encourage collaborations and co-creation of projects would help develop and advance basic science communication research and practice specifically, and the broad science communication ecosystem generally. |

Opportunities and Priorities of the Community, for the Community, and by the Community.

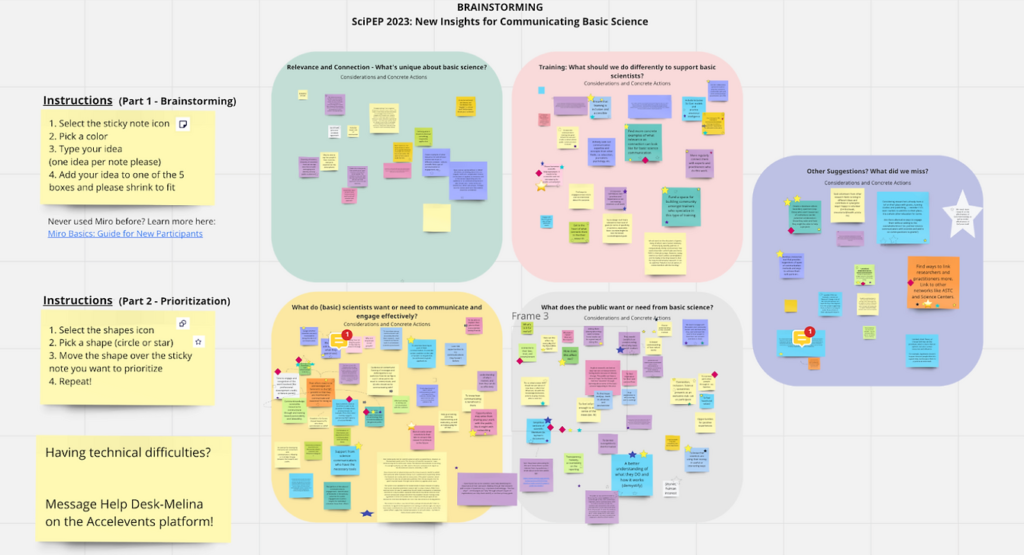

The final session was a conference-wide brainstorm about next steps and “how to take action together,” said Keegan Sawyer. To kick-off the brainstorming, Marina Joubert (Stellenbosch University) shared an exciting new opportunity – a call for papers for a special issue in the Journal of Science Communication on Communicating Discovery Science and an international symposium to be held in South Africa in 2024. Then, conference attendees were invited to share priorities, considerations, and concrete steps for action on a Miro board, an online white board space (Figure 3). The MIRO board with all submitted suggestions can be viewed here. Following the brainstorm, Erika Shugart (National Science Teaching Association), Daren Ragojo Ginete (Science Philanthropy Alliance), and Jory Weintraub (North Carolina State University) joined in discussion as expert rapporteurs. In a discussion facilitated by Keegan Sawyer, the rapporteurs synthesized broad trends in each of four thematic areas:

- Relevance and connection;

- (Basic) scientists wants or needs to communicate effectively;

- Training to support basic scientists; and

- Public wants or needs from basic science.

Relevance and Connection – what’s unique about basic science?

- Define what relevance and impact mean for basic science.

- Experiment with different approaches to establish relevance and connection, perhaps focusing on highlighting the process of discovery or on “scientists and researchers as people beyond their research work.”

- Center the importance of diversity. Involve people with a diverse skill sets, knowledge, contacts, and backgrounds.

What do (basic) scientists want or need to communicate effectively?

- Ask and listen to basic scientists about what they want and need. Engage with scientists to learn how to better serve them.

- Incentivize science communication. “Make it clear” to basic scientists why it is important and also develop reward structures, such as “adapting the tenure and promotion process to value science communication”.

- Document and share how science communication and engagement impacts or changes basic scientists.

- Lower the risk. Basic scientists need spaces where they practice and get feedback without worry as they are learning and improving.

What does the public want or need from basic science?

- Communicate how science is connected to people in practical ways. Answer questions such as “‘how does science affect my everyday life, and how can I use it for informed idea making?’

- Learn more about publics interests and what they understand. Does the public understand science? Is it just a general sense of what’s going on? Do they understand scientists?

- Do more research on what elicits emotional responses to basic science (e.g., excitement, joy, hopefulness).

- Explore how to promote a sense of belonging. How do we communicate or engage with publics so “they can be a part of” basic science and/or communicating about science?

Training: What should we do different to support basic scientists

- Incorporate science communication training into the process of preparing scientists –in both undergraduate and graduate curricula. Keep pushing for this to happen.

- Make science communication training a part of professional development for established scientists.

- Create and fund spaces for science communication trainers to explore, develop, and share best practices for communicating basic science.

- Ask the science communication community to provide basic scientists with the tools they need to communicate effectively. More support is needed, including facilitating access to new developments in science communication research and practice.

Sawyer observed that many ideas in the MIRO board are more conceptual than concrete and asked the rapporteurs “what makes it so difficult” to articulate “shovel-ready” actions. Weintraub pointed out that practitioners have been working to address many of the ideas in the MIRO board for a long time. “We know the reality [that] lack of resources, lack of administrative support,” contribute to making concrete actions challenging. Shugart pointed out that many suggestions indicate strong desire for more scientist-communicator connections, but there are limited spaces and efforts to encourage such collaborations. She emphasized the need to think carefully about how groups are brought together “so they leverage each other more.” Ginete offered that “communicating discovery science requires systems solutions. This is not just a one person, one entity, one institution problem.” It’s hard to determine where all the different directionalities and pressure points exist. But, this is not unsurprising. What is existing, Ginete emphasized, is there are so many ideas and a lot of passion and desire to advance basic science. “I think we could all do different things and hopefully at some point we can tip the lever towards our goals for discovery science.”

The final thoughts and summary of SciPEP 2023 can be read in SciCommBites’ Executive Summary.

Written by Jacqueline Goldstein, Lauren Budenholzer, and Keegan Sawyer

Edited by Sandra McLean, Kirsten Giesbrecht, Kay McCallum, and Niveen AbiGhannam