What Happens To Pandemic Policy When People Don’t Trust Scientists?

By Tony Van Witsen

Title: Follow the scientists? How beliefs about the practice of science shaped COVID-19 views

Author(s) and Year: Thomas G. Safford, Emily H. Whitmore and Lawrence C. Hamilton, 2021

Journal: Journal of Science Communication

https://scholars.unh.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2217&context=faculty_pubs

| TL;DR: Eroding trust in scientists may have reached a peak during the COVID-19 pandemic. This seems to have affected willingness to follow public health guidelines as well. Why I chose this paper: Decline in the public authority of science is an increasingly consequential problem. It seems important to me to understand why it’s happening. |

The Problem

“More shutdowns are avoidable, but the public needs to trust science,” said Dr. Anthony Fauci in August 2020, just a few months after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

If only! Health authorities, confronted with a once-in-a-century challenge, had to make quick decisions under the pressure of developing and still unsettled science. This frequently spotlighted disagreements among scientists that would be confined to low-profile peer reviewed journals under normal circumstances. Dr. Fauci was only one of many scientists whose plea to “follow the science,” as the term goes, was often met with skepticism, distrust and noncompliance. For many scientists, this response renewed concerns that (a) the public doesn’t understand how science works and (b) doesn’t show proper respect for scientific authority. In June 2020, for example, members of the prestigious National Academy of Sciences criticized the Trump administration for “denigration of scientific expertise and harassment of scientists. The dismissal of scientific evidence in policy formulation has affected wide areas of the social, biological, environmental and physical sciences.”

The Research

When people have less trust in science this frequently leads to less respect for science-driven policies. In the past, this has happened on issues such as vaccination, climate change and the 2016 Zika virus. More recently, researchers Thomas Safford, Emily Whitmore and Lawrence Hamilton at the University of New Hampshire wondered whether the pandemic-driven suspicion of some COVID-19 science might be driving a similar disrespect for pandemic and lockdown guidelines. In two surveys taken in New Hampshire in March and July 2020, they asked a question meant to measure trust or distrust in scientific honesty: “Do you agree or disagree that scientists adjust their findings to get the answers they want?”

They followed this with four questions about attitudes toward the pandemic.

• Whether people worried someone in their own family might catch COVID.

• If they believed the worst was yet to come for COVID

• How often they used face masks in public.

• Whether the government should emphasize containing COVID or restarting the

economy.

Two more questions inquired whether people approved of the way President Trump and New Hampshire Governor Christopher Sununu handled the pandemic.

Results

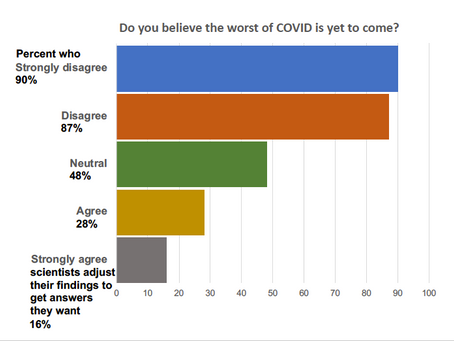

They found a strong, consistent pattern: on issue after issue, people who questioned scientists’ integrity also rejected science based COVID assessments by large margins as well as guidance on masks and lockdown policy. For example, 95% of those who strongly disagree with the statement that scientists adjust their findings thought controlling the virus should be the government’s highest priority. But only 14% of those who think scientists adjust their findings prioritize controlling the virus. Lower trust in scientists was also associated with dismissal of warnings that the worst is yet to come and compliance with mask wearing.

16 per cent of respondents who thought scientists do adjust their findings thought the worst of COVID lies ahead

Distrust of scientists also strongly correlated with party affiliation and support for Trump, characteristics which were also associated with attitudes toward pandemic policy. Odds of thinking the worst of the pandemic was yet to come were 94% lower among Republicans than among Democrats. Similarly for commitment to masks and giving priority to fighting the virus vs the economy. Those who distrusted scientists approved of Trump by 77 per cent. This is complicated by the fact that previous research found Republicans were already less likely to worry about the COVID threat than Democrats, affecting their likelihood of wearing masks or worrying about the pandemic. However views of more educated people of both parties tended to converge, a clue that pandemic attitudes are rarely driven by political identity alone.

What it means

The authors support using science to guide policy, especially during a pandemic, but they also think this increased the visibility of pandemic-related scientific research and the scientists who were involved. The higher profile of pandemic scientists had the unplanned effect of making them more of a target for distrust, possibly because increasing numbers of people saw them as normative decision-makers, more like politicians with value-based agendas rather than disinterested professionals just doing their jobs according to uncontroversial objective standards.

Science communicators know through long experience that the quality of published scientific findings alone don’t always inspire nonscientists to trust in them. Trust is affected by social and psychological components and effective science communication needs to recognize that people sometimes trust or distrust science for reasons that aren’t immediately obvious. For example, the views of more educated people in their survey tended to converge, regardless of how much they did or didn’t trust scientists. On the other hand, researchers who studied climate change found the opposite effect: increasing education didn’t bring the believers and doubters together but paradoxically, drove them further apart. The authors believe it’s important to get a better handle on whether trust is driven by discipline, by institution or perhaps, by the kind of scientific controversy involved.

Edited by Niveen Abi Ghannam, Jacqueline Goldstein

Cover image credit: Tim Dennell Creative Commons