What’s the justification behind a hot take?

By Kay McCallum

Title: Reasoning on Controversial Science Issues in Science Education and Science Communication

Author(s) and Year: Anna Beniermann, Laurens Mecklenburg, Annette Upmeier zu Belzen, 2021

Journal: Education Sciences (https://www.mdpi.com/2227-7102/11/9/522/htm)

| TL;DR: It’s easy to assume people who disagree with established science are just arguing from subjective values, fallacy, or ignorance. Turns out, their arguments may have more integrity than we give them credit for. Why I chose this paper: I spend a lot of my free time researching ideological rabbit holes and the rise in anti-intellectualism in North America – and I’ve even encountered Twitter trolls on topics that shouldn’t be contentious. It’s easy to dismiss them, but effective change of minds starts with empathy, and this paper highlights how people come to conclusions on science, good and bad. |

At the heart of science communication is the intent to bridge the gap between scientists and society, especially in addressing socioscientific issues – scientific questions that broadly impact society, like how to combat climate change, use stem cell research, or develop artificial intelligence, to name just a few. These are difficult, complex issues that require a sufficient amount of scientific literacy for communities to have productive conversations and make informed decisions.

But conversations about what to do regarding an issue can be near-impossible to have when the scientific facts themselves are considered contentious by segments of the public. These topics are controversial science issues: issues that the public has made into a debate, even if there is no debate in the scientific community. They’re the sort of topics we may not talk about at family gatherings to keep the peace, but that science communicators, as informers of the public, don’t have the luxury of avoiding.

It’s easy to dismiss science deniers as angry, ignorant ideologues, perpetuating some sort of political agenda – but is that actually true?

The Details

What are the reasons behind the public’s opinions on controversial science issues? Do certain attitudes correlate with certain types of justifications? Are some justifications used more often for specific controversial topics? How are attitudes and justifications related to other factors, like understanding of science or religiousness?

To answer these questions, Beniermann and colleagues created a survey that was advertised on German social media in the comments of science communicators’ Tweets, anti-vax Facebook groups, and YouTube videos on GMO foods. Respondents rated their agreement with statements on five controversial science issues (vaccines, GMOs, evolution, climate change, and COVID-19); provided a reason for their rating; and rated their attitudes on religion, their understanding of how scientific research works, and their propensity for conspiratorial thinking. These data were then categorized and analyzed for possible correlations.

These responses were classified into types of justifications: subjective arguments (based on the respondent’s personal beliefs), deferential (referred to a body of research, or lack thereof), or evidential (provided empirical arguments based on real-world examples, or theoretical arguments that weigh up the evidence). Subjective arguments constituted the smallest fraction of justifications. Notably, most arguments relied on referencing a body of research (whether valid or not), especially in justifying claims about climate change, evolution, and vaccinations. Empirical arguments were more common than theoretical (especially regarding COVID-19).

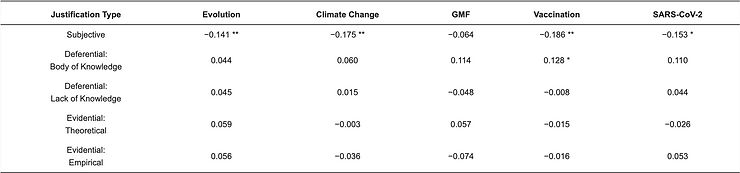

So how do the types of justifications correlate with respondents’ agreement with the science? As shown by the correlations in Table 1, not much. Subjective arguments weakly correlated with rejecting scientific consensus; and in the question on vaccines, deferential arguments correlated with accepting scientific consensus. Other arguments, however, generally do not correlate with agreement or disagreement. In fact, positions on genetically modified foods, the most controversial issue studied (with less than 60% of respondents agreeing with the science), do not correlate with any argument type.

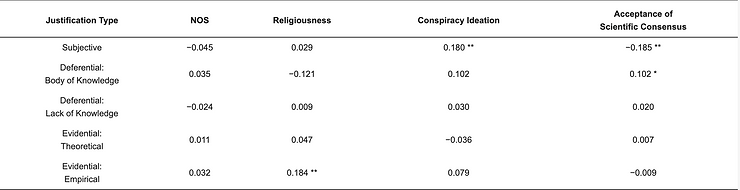

External factors – things like respondents’ views on religion and conspiracies, that don’t directly relate to the survey questions – seem to play a bigger role, as shown below in Table 2. Generally, people who had a better understanding of the scientific process agreed with the science, and people who were more religious or prone to conspiratorial thinking disagreed. Importantly, conspiracy ideation correlated more strongly with disagreement than religious attitudes, and it was weakly correlated with subjective arguments.

The Impact

Most days, it seems that science communicators are fighting an uphill battle – just ask any epidemiologist on Twitter how their mentions have looked these last few years. Faith in institutions has fallen, science has been made a partisan issue, and mistrust in scientific experts is at an all-time-high. People can now funnel into – or even opt into – completely different realities, defined by echo chambers where content only reaffirms positions they already hold, conspiracies provide meaning for the state of an increasingly unjust world, and alternative facts exist for any set of data.

For science communicators, it’s difficult, exhausting, and thankless to combat misinformation. Because of this, it’s easy to forget that amidst all the bots and spam accounts, there are people too – people who may have justifications to distrust institutions, or may not have as strong an understanding of how scientific research works. Not every dissenting voice is operating from a place of malice or mischief.

In this paper, the validity of respondents’ arguments were not addressed, only the type of argument. It is possible that many of the arguments rejecting the scientific consensus are without merit. But people don’t come to conclusions in a vacuum. By understanding the justifications behind them, we as science communicators can better meet our audiencewhere they are, address misconceptions that cause faulty conclusions, and lead to a more scientifically literate society.

Edited by Edited by Teodora Stoica and Jacqueline Goldstein

Cover image credit: Photo by mohamed_hassan from Pixabay