Scientists want to get out of the lab and into public engagement

By Sarah Ferguson

Title: Scientists’ incentives and attitudes toward public communication

Author(s) and Year: Kathleen M. Rose, Erza M. Markowitz, Dominque Brossard, 2020

Journal: Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences (open access)

TL;DR: Scientists at land grant universities broadly support public engagement with science and want to do more than just share facts, but still don’t feel supported by institutions and peers in their communication efforts.

Why I chose this paper: I work in academia, so I would like to help academic scientists engage with the public. I chose this paper to understand how academic scientists feel about public engagement and what might be stopping them from engaging with the public.

A common stereotype of scientists is that they like to stay locked in their labs inside the ivory tower of academia, but a recent article has found that they actually might be trying to climb down to engage with the public. However, these scientists still aren’t getting the support they need on the ground to continue their public engagement efforts.

According to a 2020 survey, academic scientists strongly support interactive science communication efforts. The same survey also found that younger faculty place even more importance on public engagement in science, indicating a possible shift in attitudes towards scientific public engagement. Despite this support, most scientists reported that public engagement was not important to their peers or superiors, making public engagement an uphill battle unless institutions make a concerted effort to support and expand public engagement.

The Methods

The authors in this study focused on land grant colleges and universities to form a more complete picture of scientists’ views, involvement and capability of public engagement. The authors favored land grant institutions because these colleges and universities have long standing traditions of using research to provide programs and support to surrounding communities, so the scientists should also be strong supporters of public engagement. Additionally, there is at least one land grant institution in every state, allowing for a greater cross section of scientists to be reached.

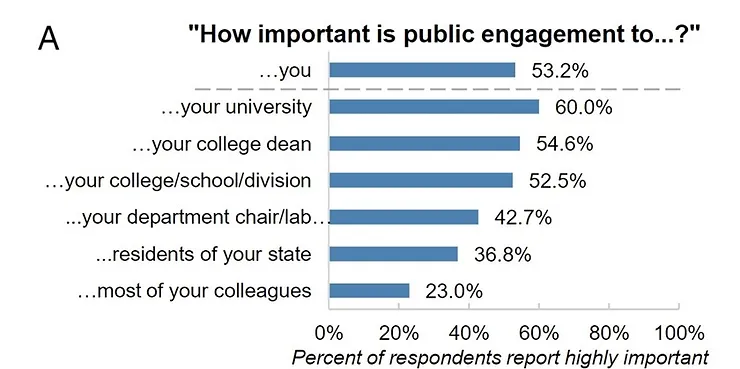

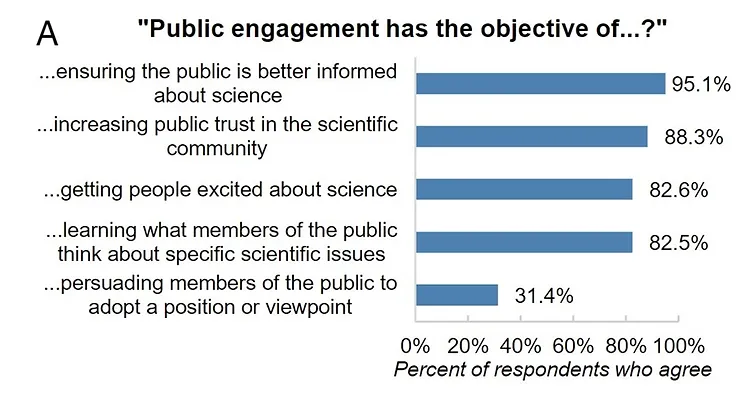

From May to June of 2018, a research team contacted over 100,000 science faculty from all 73 land grant institutions and invited them to complete a survey about science communication. The survey included questions about how important scientists felt public engagement was to themselves, their peers, their superiors and their state’s residents. The survey also asked the scientists about the objectives of public engagement.

After collecting completed surveys, only institutions with 20 or more completed surveys that accurately represented the institution’s faculty gender distribution were included in the study. A total of 6,242 surveys from tenured or tenure track scientists from 46 land grant institutions were included in the final sample.

Survey answers were then tallied. The research team also analyzed how age and gender predicted a scientist’s attitude towards public engagement.

The authors note that scientists who highly value science engagement may have been more likely to respond to the survey while those who do not value science engagement might not have responded.

The Findings

Scientists overwhelmingly supported public engagement with science with 98% reporting participating in at least one science engagement event during the year.

Figure 1 highlights how 53% of academics reported that science engagement activities were important to them. Younger faculty placed even more importance on public engagement.

However, despite most scientists reporting high levels of personal support for science public engagement, only a minority (43%) reported that higher level employees, like department chairs, had science engagement as a priority at their institution. An even smaller number (23%) of scientists thought that their colleagues valued science engagement. Scientists also didn’t feel that residents in their surrounding community valued science engagement, with only 37% reporting that residents found science engagement highly important.

On a slightly more positive note, scientists responded that the objectives of public engagement should be more than to just inform or persuade the public, marking a departure from the deficit model of science communication. Instead, scientists picked a broader range of science communication objectives. Figure 2 shows that scientists said that public engagement should “get people excited about science” (83%), “increase public trust in the scientific community” (88%) and “learn what members of the public think about specific issues” (82%).

Scientists also reported strong confidence in their ability to explain science concepts to a lay audience (67%) and to adjust to different audiences (62%). However, most scientists (58%) did not feel comfortable responding to criticism from an audience.

The Findings

The fact that more scientists, and younger scientists are considering broader objectives for science engagement, instead of just persuasion, hints towards more productive engagement efforts, which could have a marked impact on public support for science and scientific institutions. Though scientists reported valuing science engagement and participating in engagement events, the authors point out that the lack of support that scientists feel from those higher up in their institutions and their peers could hinder their success in creating meaningful science engagement. In other words, the scientists currently involved in public engagement might be the ones who would be involved regardless. In order to get more scientists to participate in public engagement and to get current public engagement to go further, institutions need to make their support known. This entails a cultural shift in academia where endeavors in public engagement are valued just as much as research endeavors, with support provided to match. If scientists are to heed to call for more effective public engagement, institutions need to provide practical science communication training and resources to their science faculty, as well as recognition and respect for public engagement.

Edited by: Andrea Isabel López and Niveen AbiGhannam

Cover image credit: Kampus Production, Pexels